Having fallen under their spell, he failed to notice that the water rose higher and higher until one day, the storm swept right through his house and washed Danny and his new friends out. Ever since then he has been out there in the stormy sea, trying to ride the waves and stay afloat. Down and Out in the South is about Mo’s pain, who lived up in Alaska, where Santa Claus is supposed to be – though Mo has never seen him, neither before nor after his wife and little daughter drowned in the waves of the ice cold Yukon River. Their bodies were never found. Mo thinks it must have been the seals or whales that ate them up. He left everything he had in Alaska and traveled down to Atlanta, a city that has no river. He found a job as a tractor trailer driver there and he would still be doing that if it hadn’t been for another accident. One night near East Point, a group attacked him and someone hit him on the back of his head with a brick. Now Mo is blind and he is drifting about in the same stormy water as Danny, where he can sometimes hear the voices of his wife and daughter calling him from a distance.

Down and Out in the South is also about Tami’s pain. She was leading a normal family life in a normal home until her son committed suicide. Her heart broke and her will to live started to wither. Her husband worried that Tami wanted to be reunited with her son. He became afraid to leave her alone, so how could he then go to work? Since they still had to eat, he committed a crime that landed him in prison. Without his income, Tami lost her home and found herself with Danny and Mo in turbulent waters. If we care to look in these waters, we would see many others. We might see Johnny, whose mental issues got really bad after his daddy died, and who tried to comply when a voice ordered him to commit suicide but failed; or Carmen, who at 64 is as dirt poor as the day she was born; whose first husband was abusive, and whose second husband died of cancer and left her with nothing after the hospital bills were paid; and we’d undoubtedly see way too many others as well.

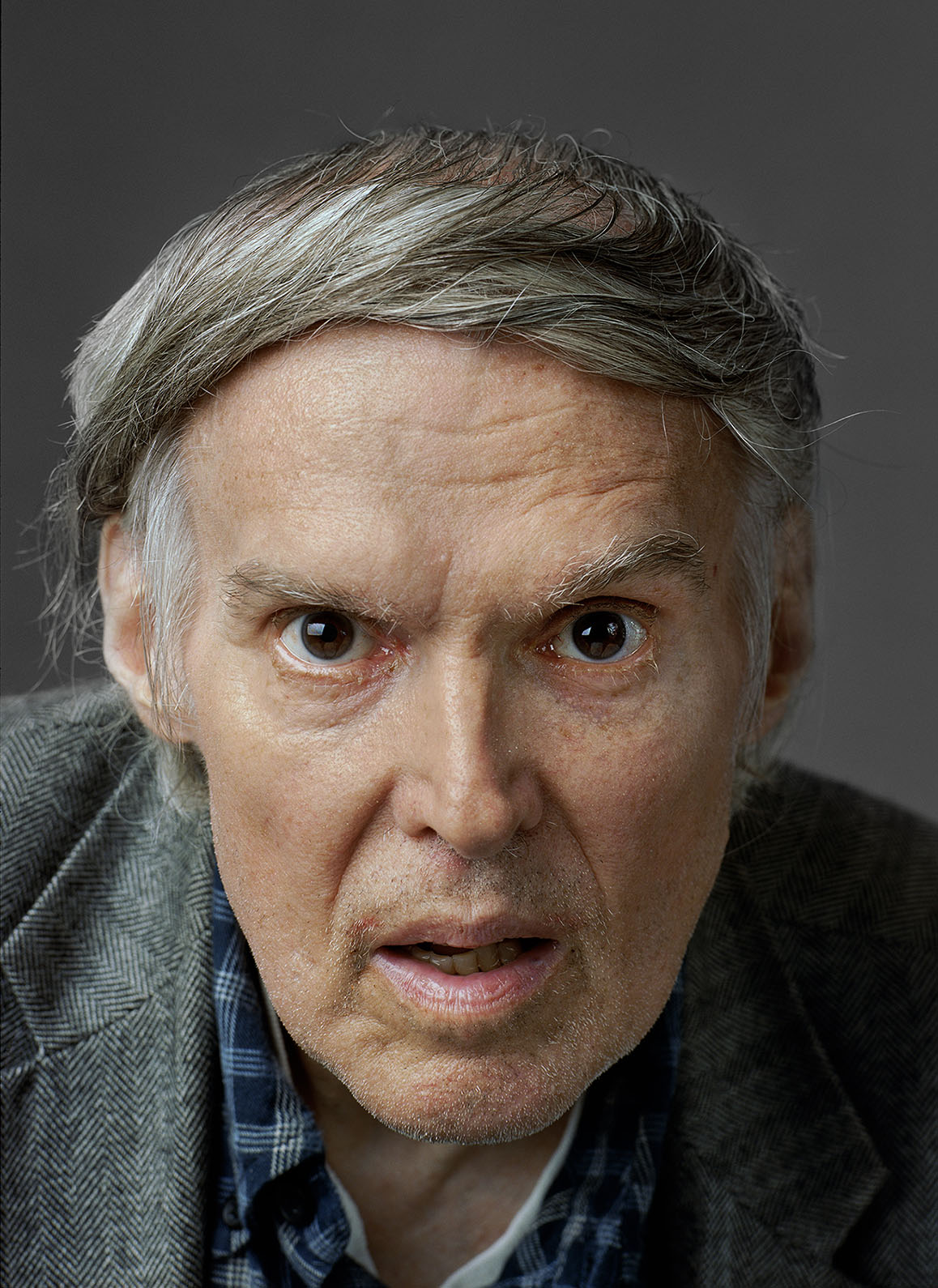

In the meantime, while all these men and women are floundering in the waves, we, people with a home, huddle in our houses on our own little islands trying to be happy and safe in the intimacy of our families, while around us the storm rages on. Sometimes, in the twilight, Danny or one of the many others gets washed up on the shores of our island. We are alarmed by our dog barking and rattling its chain, or perhaps it is not the dog but our conscience. It bothers us, so we tell him to get off our property. He replies: “But I’m so tired” and “I’m too old to be out here.” But does this man have no respect at all? Doesn’t he understand that we too have to struggle to keep our houses and our heads above water? He holds on and stares at us with big blue eyes. Now we become seriously aggravated and we shout: “Go! The more I feel I have to share, the less I want to!”

After all, it’s our small island and life and we have every right to decide what we do with it. We may not share with him when he needs it, but we may well decide to help in our own chosen time and place. While we are contemplating this, a big wave breaks on the shore and pulls the castaway back into the stormy waters – and if he hasn’t drowned then he is still floundering about out there, just like Mo and Tami and Johnny and Carmen and so many others.

PROJECT DESCRIPTION

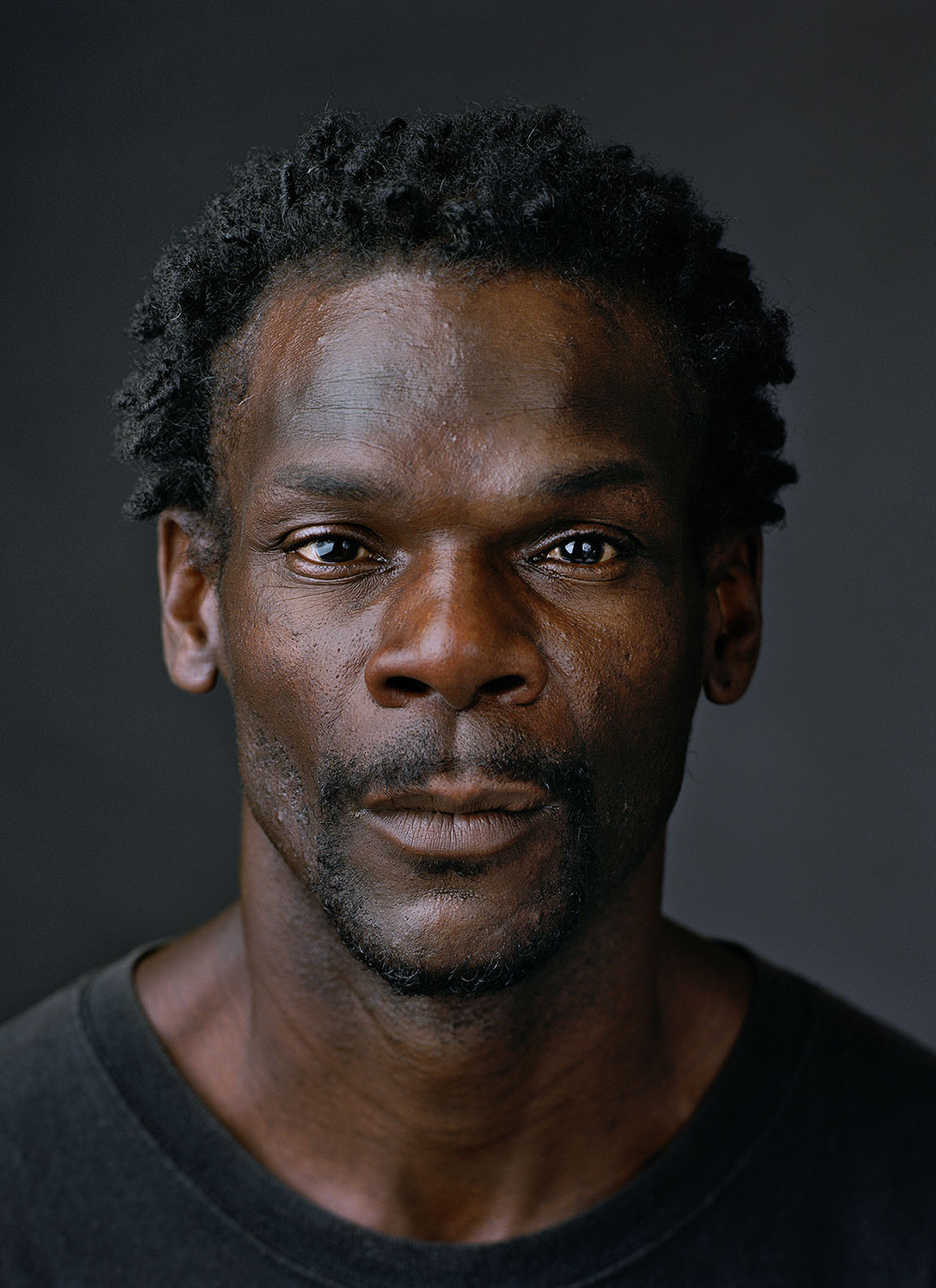

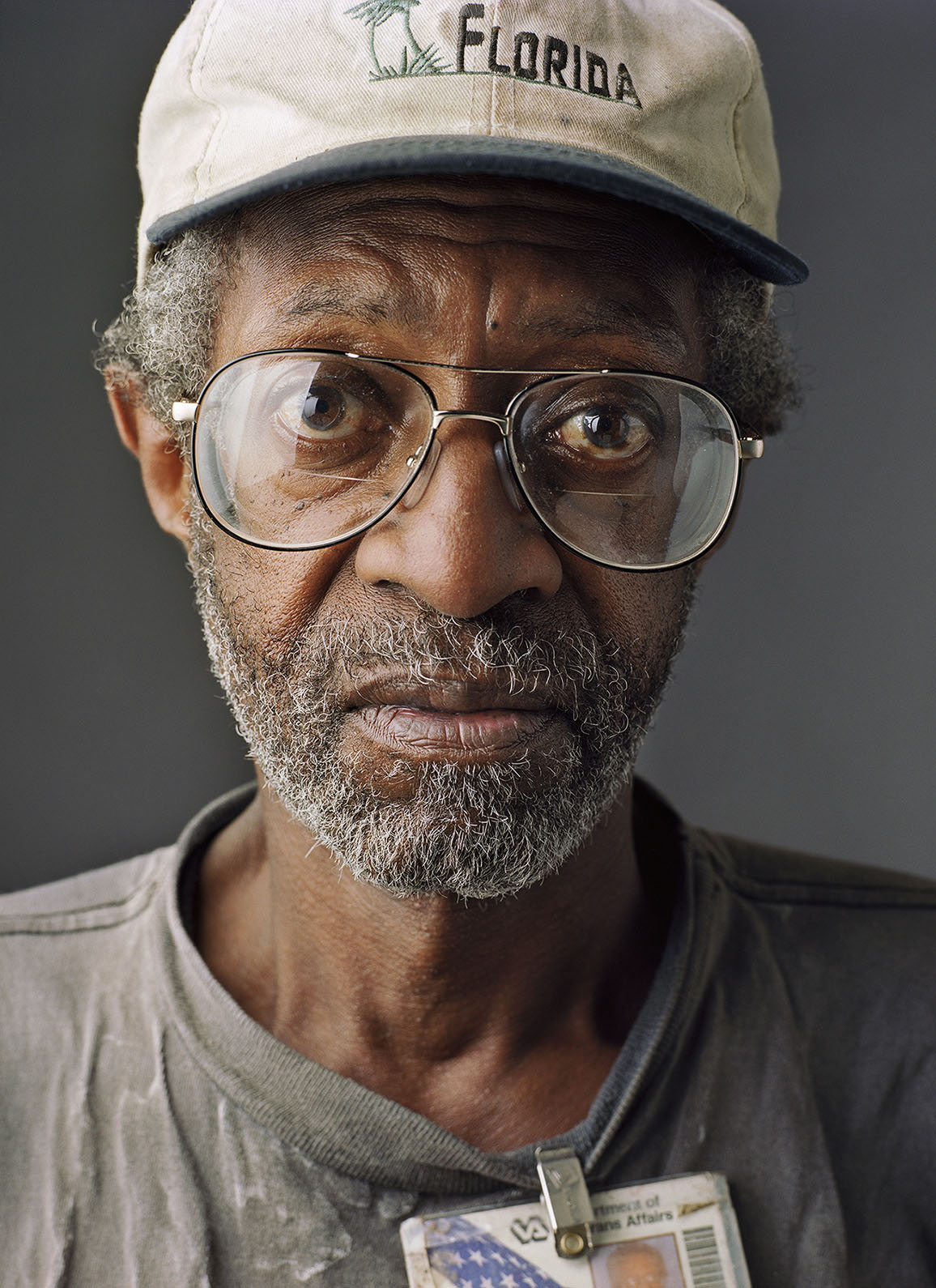

The project started in September 2010, when 701 Center for Contemporary Art (CCA) in Columbia, S.C. (U.S.) invited me as an artist-in-residence. A board member of the CCA suggested homelessness as a possible subject matter for me to explore through photography during this residency. Initially, I was skeptical because society’s outcasts have been photographed very often, and I worried that I had little to contribute to existing images. However, after some consideration, I came up with a different approach: to photograph people who are homeless as I would photograph any other member of society. That implied not scouting out the most picturesque people I could find, with beards and hats, and leaving out the typical paraphernalia, such as shopping carts and sleeping bags. My approach also implied not photographing them in dramatizing black and white — imagery so often associated with portraits of homelessness. Instead of presenting them as The Other, and thus, by default, different from us, I wanted to photograph them in a studio setting, against a neutral backdrop, focusing on their individuality rather than on stereotypes. In essence, I want to show who they are rather than what they are labeled.

I set up a makeshift studio in offices and rooms in organizations that serve homeless people in Columbia, S.C., Atlanta, Ga., and the Mississippi Delta. I felt that the choice of three different habitats – a medium-sized city, the Southern metropolis and a few rural towns – in three different Southern states would result in a fair degree of representation of homelessness in the U.S. South. In total, I photographed approximately 100 homeless men and women. Of these, 42 portraits were selected for this book.

In Columbia, and to some extent in Atlanta, I worked with an outreach worker of a homeless organization in that city. We approached people on the streets, in parks, and in the library, for example. The outreach worker would introduce me and explain what I was doing. If the person consented to the brief interview and to having a photograph made, we would go immediately to my make-shift studio and start right away, without any clean up or other aesthetic arrangements.

In Atlanta, I approached most men and women while they were coming in off the streets for their free meal and a bed in one of the organizations that regularly feeds and shelters homeless people. After introductions to the large group, I would approach people who I wanted to photograph. I conducted the photography and interviews after the person’s meal, in the studio set up just a few yards from where they were eating or standing in line.

A few of the people I photographed in the Mississippi Delta were staying in a shelter for a longer period of time, but even then, they made no special preparations for the photoshoot. The people you see in this book look just like they did when I first met them.

Book

A book containing 42 of the portraits called “Down and Out in the South” and an iBook with the same title, including the interviews and some fragments from a documentary movie will be published in the May 2013 by Ipso Facto (IF), Utrecht, The Netherlands, and will be presented at the Naarden Fotofestival. Distribution: via this website and via Idea Books (Amsterdam).

Atlanta-based writer James Swift will write an introduction. Over the years, his portfolio has expanded to include features on rural poverty, the American education system, autism spectrum disorder research and gay and lesbian rights, among scores of other cultural issues and events. He is the author of two books, 2009’s How I Survived Three Years at a Two-Year Community College: A Junior Memoir of Epic Proportions and 2010’s Mascara Contra Mascara: A Tale of Two Masks.

Exhibition

In May – June 2013, the series will be exhibited at the Naarden Fotofestival in Naarden, The Netherlands. – In October 2012, Down and Out in the South was shown in Atlanta, GA, in a series of six video projections during ACP (Atlanta Celebrates Photography) in a public installation at the Digital Arts Entertainment Lab at Georgia State. – In that same period, a print show was held in the Big House Gallery, 211 Peter Street SW, Atlanta, GA 30313. For further info, see ACP (here) – Earlier, a selection has been shown in the JJ-W Hotel (“Root” room), Tainan City, Taiwan, May 21 – June 21, 2012 (as part of group exhibition ‘Non-Sleep in Non-Home – Living in Art and Art Living in the JJ-W Hotel’).

Online

Grants

The project, the book and the exhibition Down and Out in the South have been made possible with financial support from the Mondriaan Fund and from the Stichting Sem Presser Archief, both in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

For the people I photographed

I sent to a hard copy of his or her portrait to every person I photographed for this project. Many of these photographs have been returned to me as undeliverable. To anyone who has not received the promised copy: please contact me (here) and give me your name and address, and I will try it once again.

Special thanks

Special thanks to Jennifer King, Tom Bolton, and to the many homeless men and women who agreed to be interviewed and photographed for this project.

Financial support (including for the book) from: 701 Center for Contemporary Art, Columbia, SC; Mondriaan Foundation, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; The Netherlands Embassy, Washington, D.C.; Stichting Sem Presser Archief, Amsterdam, , The Netherlands.